Research

- Framing my research career

- Current research

- Past research, trajectory, and main research lines

- Senior researcher stage

- RL1: Robust and scalable adaptive unfitted finite element methods with application to additive manufacturing

- RL2: Advanced numerical methods for the large-scale simulation of high temperature superconductors

- RL3: Software engineering of large scale scientific applications, open source scientific software

- Post-doctoral researcher stage

- Pre-doctoral researcher stage

- Senior researcher stage

- References

Framing my research career

In this introductory section I pinpoint the field of application of my research, and some general features of the problems within this field that my research targets. This will help the reader understand my trajectory and the main RLs I have carried out, which are covered in Section Past research, trajectory, and main research lines.

As a researcher working in the CSE field, I contribute to the development of computational models, algorithms, and software for several application problems. All of these share three common general features (not restricted to, though):

The physical phenomena to be simulated are governed by a (potentially highly nonlinear) PDE, or more generally, by a system of PDEs. These phenomena may span multiple temporal and spatial scales, and involve different physical models.

The system of PDEs is discretized by means of the FEM. Thus, broadly speaking, the simulation pipeline encompasses three main ingredients: mesh generation and partitioning, space-time FE discretization, and solution of (non)linear system(s) of equations.

These are application problems with ever increasing modelling accuracy requirements, and thus highly demanding from the computational viewpoint. In particular, simulation pipelines grounded on highly parallel, algorithmically scalable algorithms and HPC software, thus able to efficiently exploit the vast amount of computational resources in current petascale supercomputers, are required in order to achieve the aforementioned modelling requirements.

The increasing levels of complexity both in terms of algorithms and hardware make the development of scientific software able to tackle the aforementioned features, while running efficiently on state-of-the-art numerical algorithms on HPC resources, a scientific challenge in itself. A part of my research work has been devoted towards the achievement of this goal. This is motivated by the fact that research on advanced, newly developed FE discretizations and solution algorithms for the HPC solution of CSE complex problems frequently requires innovative solutions on the software engineering aspects of a numerical software package as well, and that these latter also represent an important contribution to other researchers working in the CSE community.

Current research

Work in progress ...

Topics:

Hybridizable finite element methods for general polytopal meshes (HDG, HHO, VEM, etc.).

Scalable preconditioning for these schemes (h/p geometric multigrid approaches, hybrid multiscale domain decomposition, etc.).

Exploiting the synergy among Artificial Neural Networks and the numerical solution of PDEs.

Scientific Machine Learning approches for large-scale inverse problems.

Physics-informed Neural Networks with application to prediction of bushfire dynamics.

Numerical methods for geophysical flows with application to Numerical Weather Prediction.

Past research, trajectory, and main research lines

This section overviews my research trajectory and main RL pursued. This will be presented in reverse chronological order, and split into three differentiated stages, namely: senior researcher, post-doctoral, and pre-doctoral stages. We note that that there is not necessarily a one-to-one correspondence among stage and position at an academic organization. The division into stages is done accordingly to the level of professional independence and academic maturity that was expected from me at the corresponding organizational units.

Senior researcher stage

This period spans 2016-2020. Early 2016, I was promoted as senior researcher at the CIMNE, position which I held until late 2019, concurrently with my position as adjoint professor at UPC. Then, early 2020, I moved to the School of Mathematics at Monash University (Melbourne, Australia), where I was appointed as senior research fellow (Level B) for a 3-year period after winning an international competitive call for candidates. During this period, I have carried out three main RLs which are labeled as RL1-RL3 below. RL3 should be regarded as a cross-cutting, continuous RL , on which the advances of the other RLs are grounded on, and vice-versa.

RL1: Robust and scalable adaptive unfitted finite element methods with application to additive manufacturing

Research line statement

This main research goal of this RL was the development of novel numerical methods for the accurate, computationally efficient and scalable simulation of large-scale transient multiscale PDEs on complex evolving domains, with moving interfaces and/or free boundaries, with application to the simulation of metal AM processes (a.k.a. 3D printing). The traditional CAD/CAE paradigm, which relies on (semi-automatic, hard-to-parallelize) unstructured mesh generators for spatial discretization, and the (inherently sequential) MOL for time discretization, presents a poor integration among CAD geometrical models and the PDE numerical discretization algorithms, and at the most favorable scenario, is not efficient to tackle problems on non-trivial evolving geometries, if not applicable/feasible at all; see, e.g., Fig.1. To this end, my contribution is the development of parallel-friendly advanced discretization methods based on the so-called unfitted (a.k.a. embedded) embedded finite element techniques (1, 2, 3) and their combination with highly scalable parallel linear solvers including multilevel domain decomposition (4) and AMG (5). The final purpose of this research is to speed up the main bottlenecks of large multiscale/multiphysics finite element computations, in particular, the mesh generation, mesh partitioning, and the linear solver phase. More details are given in the subsections below.

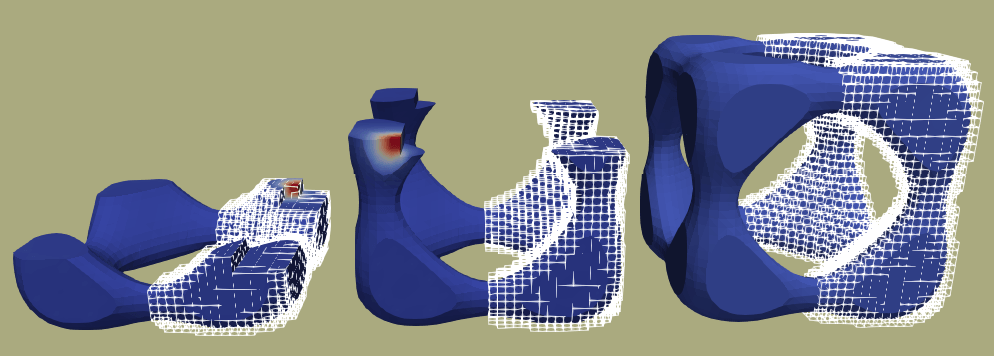

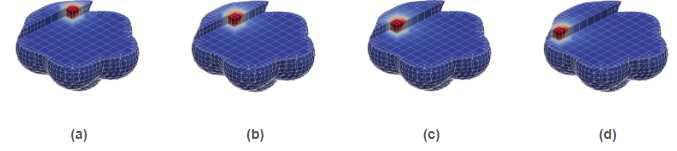

Figure 1: In an AM macroscopic simulation, one has to design a mechanism that approximates the geometry following the real scanning path of the machine. It is impractical to produce body-fitted unstructured meshes conforming with at all times. Evolving geometries jeopardize the applicability of traditional simulation workflows. The proposed solution combines tree-based adaptive background meshes for the functional discretisation and cell-wise sub-meshes for integration purposes.

Figure 1: In an AM macroscopic simulation, one has to design a mechanism that approximates the geometry following the real scanning path of the machine. It is impractical to produce body-fitted unstructured meshes conforming with at all times. Evolving geometries jeopardize the applicability of traditional simulation workflows. The proposed solution combines tree-based adaptive background meshes for the functional discretisation and cell-wise sub-meshes for integration purposes.Funding

This RL was funded by means of the FETHPC-H2020 ExaQute project (spanning 2018-2021). Besides, my project proposal on space-time adaptive unfitted methods has been funded by the Australian National Computational Merit Allocation Scheme (NCMAS) 2021 call. I have the role of co-PI in this project.

In early stages, this line was (partially) funded by two large H2020 EU projects, namely the CAxMan-Computer Aided Technologies for Additive Manufacturing and eMUSIC- Efficient Manufacturing for Aerospace Components USing Additive Manufacturing, Net Shape HIP and Investment Casting projects, in which the applicant participated as a researcher. These projects do not have a strong research component, and are led by the industrial sector. However, they enabled joint collaboration efforts with leading experimental validation partners of AM computer modelling tools. These include SKLSP in Xian, China, MCAM in Melbourne, Australia, and IK4-Lortek in Gipuzkoa, Spain. Both projects have strong technology-transfer potential. They include the application of their advances to the metal AM process of several industrial use cases, such as the patented NUGEAR gearbox by STAM, Italy.

Publications

The research work I developed within RL1 has resulted in 8x research manuscripts (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) published in top quality JCR journals (Q1-ranked).

Scalable Adaptive Mesh Refinement and coarsening with dynamic load balancing via forests-of-trees

AMR is a highly appealing technique for the computationally efficient solution of PDEs problems exhibiting highly localized features, such as moving fronts, or internal boundary layers. The basic idea is simple, to adapt the mesh, possibly dynamically, i.e., in the course of the simulation, with a higher mesh resolution wherever it is needed. However, the materialization of this idea on petascale parallel distributed-memory computers is a daunting challenge in itself. Among others, mesh densification in localized areas can cause severe load unbalance. The approach that I have pursued to tackle this challenge grounds on a new generation of petascale-capable algorithms and software for fast AMR using adaptive tree-based meshes endowed with SFCs(14). SFCs are exploited for efficient data storage and traversal of the adaptive mesh, fast computation of hierarchy and neighborship relations among the mesh cells, and scalable partitioning and dynamic load balancing. In particular, SFCs remarkably offer a linear run-time solution to the problem of (re)partitioning a tree-based mesh into processors. For hexahedral meshes, the state-of-the-art in tree-based amr with SFCs is available at the p4est software (15, 16), which has been proven to scale up to hundreds of thousands of cores. This approach can be generalized to other cell topologies as well (14).

Forest-of-trees meshes provide multi-resolution capability by local adaptation. In the most general case, these meshes are non-conforming, i.e., they contain the so-called hanging VEFs. These occur at the interface of neighboring cells with different refinement levels. Mesh non-conformity introduces additional implementation complexity specially in the case of conforming FE formulations, DOFs sitting on hanging VEFs cannot have an arbitrary value, they have to be judiciously constrained. This complexity can be relaxed, at the price of a higher of number of mesh cells, by enforcing the so-called 2:1 balance constraint. Essentially, additional (balance) refinement is introduced in order to bound the ratio among the refinement levels of any two neighbouring cells. The set up and application of hanging DOFs constraints is well-established knowledge (17, 18). In a parallel distributed-memory environment, these steps are much more involved. In order to scale FE simulations to large core counts, the standard practice is to constraint the distributed-memory data structures to keep a single layer of extra ghost cells along with the local cells, thus minimizing the impact of these extra cells on memory scalability. Under this constraint, if a set of suitable conditions are not satisfied, then the hanging DOF constraint dependencies may expand beyond the single layer of ghost cells, thus leading to an incorrect parallel FE solver. To make things worse, the current literature clearly fails to explain when and why the parallel algorithms and data structures required to support generic conforming FE discretizations atop tree-based adaptive meshes are correct.

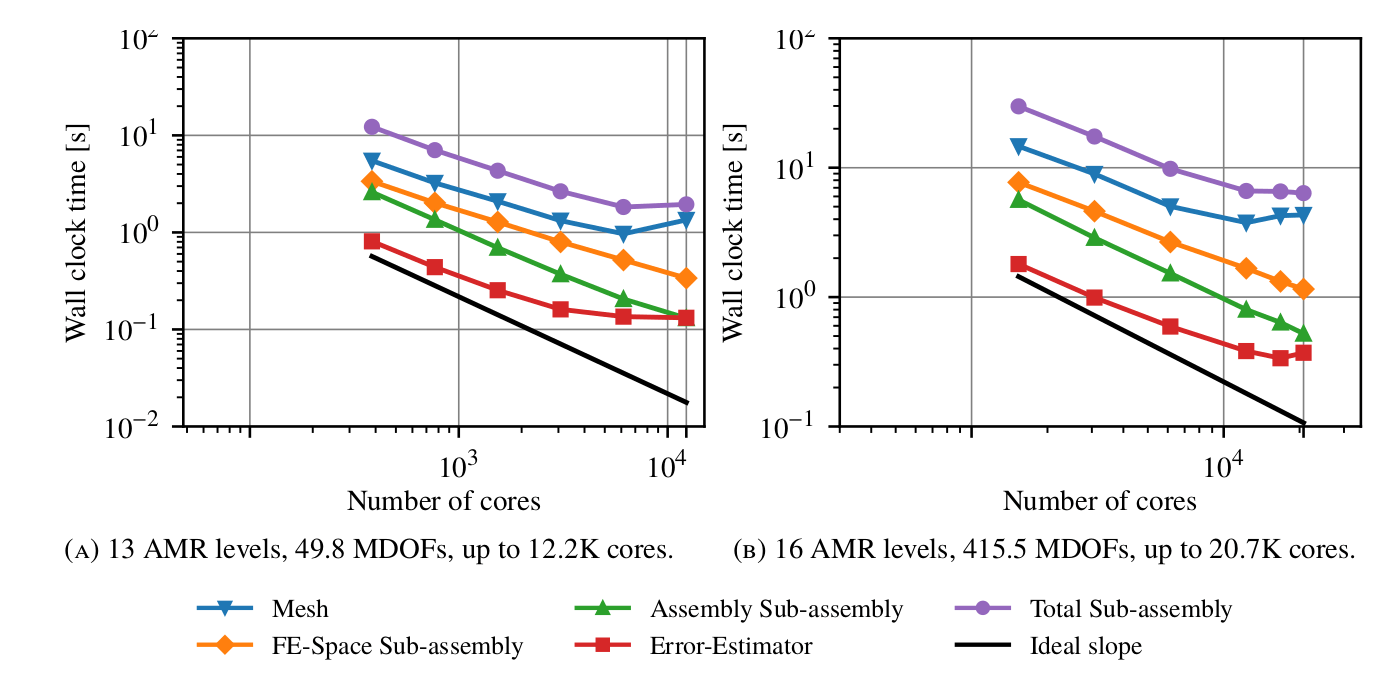

My main contribution has been to address in a rigorous way the development of algorithms and data structures for parallel adaptive FE analysis on tree-based meshes endowed with SFCs. These are part of a generic FE simulation framework that is designed to be general enough to support a range of cell topologies, recursive refinement rules for the generation of adaptive trees endowed with SFCs, and various types of conforming FEs. Starting with a set of (reasonable) assumptions on the basic building blocks that drive the generation of the forest-of-trees, namely, a recursive refinement rule and a SFC index (14), I have inferred results based on mathematical propositions and proofs, yielding the (correctness of the) parallel algorithms in the framework. A MPI-parallel implementation of these algorithms is available at FEMPAR (30). FEMPAR uses p4est as its specialized forest-of-octrees meshing engine, although any other engine able to fulfill a set of requirements could be plugged in the algorithms of the framework as well. A strong scaling study of this implementation when applied to Poisson and Maxwell problems reveals remarkable scalability up to 32.2K CPU cores and 482.2M DOFs on the Marenostrum IV supercomputer. Besides, a comparison of FEMPAR performance with that of the state-of-the art deal.II software, reveals at least competitive performance, and at most factor 2-3 improvements on a massively parallel supercomputer. As an illustration, Fig.2 reports remarkably scalability with a standard benchmark for evaluating the performance and scalability of AMR codes, namely the Galerkin trilinear FE discretization of a 3D Poisson problem with a discontinuity in the source term that leads to a solution that is non-smooth along a sinusoidal surface through the domain. This tough problem challenges the performance and scalability of AMR codes, as a very fine mesh resolution is required in order to reduce the error in that area. In a nutshell, the experiments starts from an initial uniform mesh, and the mesh is adapted using a posteriori error estimators across several AMR cycles until a target error criteria is fulfilled. After each cycle, the mesh and related data (e.g., temperature field) is re-distributed/migrated in order to keep the computational load balanced. In Fig.2, we provide the strong scalability on the Gadi supercomputer of the different stages summed across all adaptation levels with 13 and 16 AMR cycles. The curve labelled as "Total sub-assembly" includes the total computational cost involved in the solution of the PDE at hand. The average load per core at the last step ranges, in Fig.2(a), from 128.7 KDOFs/core to 4.08K DOFs/core, and, in Fig.2(b), from 332.9 MDOFs/core to 20.7K DOFs/core. Beyond that load/core limit, one can barely expect state-of-the-art AMG solvers to be able to reduce the computational time further with increasing number of cores, so that these are excellent scaling results for such a tough problem.

Figure 2: Strong scaling test results (i.e., global problem fixed, increasing number of cores) for

Figure 2: Strong scaling test results (i.e., global problem fixed, increasing number of cores) for FEMPAR on Gadi.This work has been published at the SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing (6). This paper substantially improves the current understanding of this topic with rigorous proofs of the computational benefits of the 2:1 k-balance (ease of parallel implementation and high-scalability) and the minimum requirements a parallel tree-based mesh must fulfil to yield correct parallel finite element solvers atop them assuming one is to keep the constraint that only a single layer of ghost cells is stored.

Relaxing mesh generation constraints with embedded methods

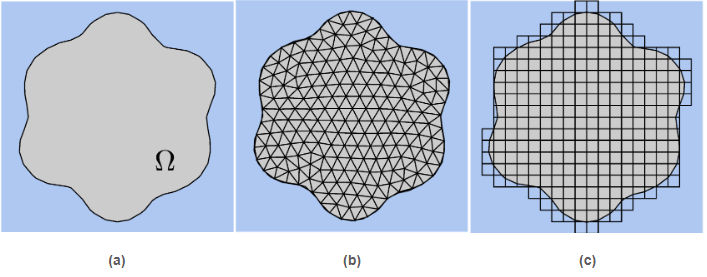

Mesh generation is known to be one of the main bottlenecks of real-world industrial FE simulations. Conventional FEs require meshes that are body-fitted. That is, meshes that conform to the geometrical boundaries of the computational domain (see Fig.3b). Constructing such grids is not an obvious task for complex geometries, it is time consuming and often requires skilled human intervention (mesh generation is estimated as 80% of total simulation time in industrial applications (19)).

An appealing alternative to circumvent this issue are the so-called embedded FE methods (1, 2, 3) (a.k.a. unfitted or immersed boundary methods). The usage of embedded discretisation schemes drastically reduces the geometrical constraints imposed on the meshes to be used for discretization. Meshes do not require to be body-fitted, allowing one to simulate problems in complex domains using structured meshes (see Fig.3c). This salient property is indeed essential for large-scale computations, since the generation of unstructured meshes in parallel and their partition using graph-partitioning techniques scale poorly (20) and in many cases require human intervention. Embedded discretisation methods are thus highly appealing, among others, for problems posed on complex geometries, and/or for which tracking evolving interfaces or growing domains in time is impractical using body-fitted meshes; see Fig.1.

Figure 3: Body-fitted vs. unfitted meshes. (a) Computational domain. (b) Body-fitted mesh. (c) Unfitted Cartesian mesh.

Figure 3: Body-fitted vs. unfitted meshes. (a) Computational domain. (b) Body-fitted mesh. (c) Unfitted Cartesian mesh.In an embedded formulation, the geometry is still provided explicitly in terms of a boundary representation (e.g., a STL mesh) or implicitly via a level-set function. It requires mesh cutting techniques that perform the intersection between the background mesh and the surface description (implicit or explicit). However, the complexity of this process is significantly lower than the one underlying an unstructured mesh generator. It is a cell-wise task, and the cell partitions are not used for discretisation but only integration purposes. At the end of the process, we have interior, exterior, and cut cells.

The aggregated unfitted finite element method (AgFEM)

However, embedded methods have known drawbacks. The most salient one, still an open problem nowadays, is the so-called small cut cell problem. Some cells of the unfitted mesh can be intersected by a very small part of the domain, which leads, in practice, to arbitrarily large condition numbers in the underlying discrete FE operators. In recent years, different approaches have been considered in order to address the small cut cell problem. Initial approaches consist in adding stabilisation terms to the discrete problem, using some kind of artificial viscosity method to make the problem well-posed; see, e.g., the cutFEM method (2) or the Finite Cell Method (3).

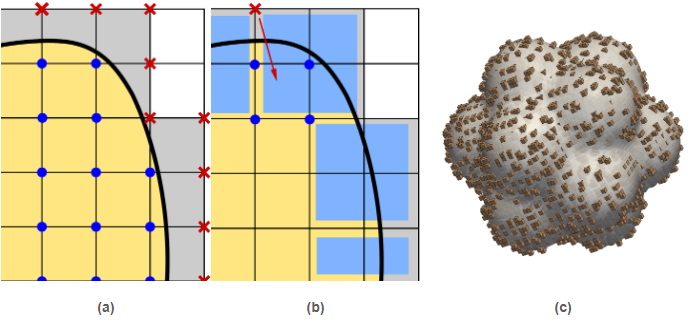

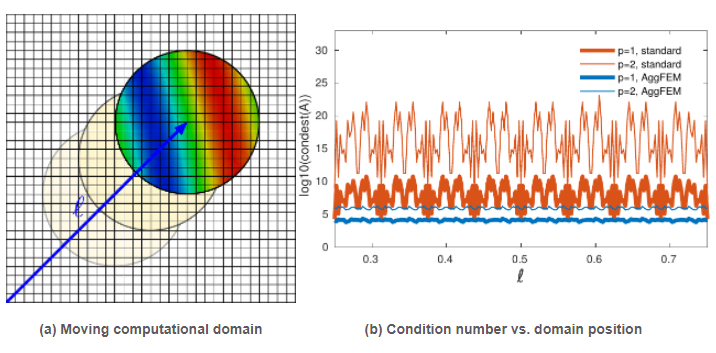

In order to avoid, among others, the introduction of artificial viscosity terms into the discrete variational problem (thus sticking into a Galerkin problem), I have recently developed in (9) a novel discretization method for elliptic problems, the so-called AgFEM; see Fig.4. In (8), I have also extended these techniques to indefinite problems in incompressible flow discretisations. Besides, I have been able to mathematically prove for both the elliptic and indefinite cases that the AgFEM formulation shares the salient properties of body-fitted FE methods such as stability, condition number bounds, optimal convergence, and continuity with respect data. See Figs.5 and 6 for selected numerical results.

Figure 4: (a) The shape functions associated to DOFs in the exterior of the domain (marked with a red cross in the figure) may have an arbitrarily small support in the interior of the domain. Thus, there is no guarantee that the condition number of the linear system arising from discretization is bounded. (b) AgFEM formulations extrapolate these ill-posed DOFs as a linear combination of selected interior DOFs (via suitably-defined algebraic constraints imposed into the space of FE functions). These constraints are defined by building the so-called cell aggregates (in blue), that give the name to the formulation. A cell aggregation is an agglomeration of cells composed by a single interior cell, and a set of face-connected neighbouring cut cells connected to it. (c) Visualization of the cell aggregates built by the method for a 3D pop-corn like domain embedded in a uniform Cartesian mesh.

Figure 4: (a) The shape functions associated to DOFs in the exterior of the domain (marked with a red cross in the figure) may have an arbitrarily small support in the interior of the domain. Thus, there is no guarantee that the condition number of the linear system arising from discretization is bounded. (b) AgFEM formulations extrapolate these ill-posed DOFs as a linear combination of selected interior DOFs (via suitably-defined algebraic constraints imposed into the space of FE functions). These constraints are defined by building the so-called cell aggregates (in blue), that give the name to the formulation. A cell aggregation is an agglomeration of cells composed by a single interior cell, and a set of face-connected neighbouring cut cells connected to it. (c) Visualization of the cell aggregates built by the method for a 3D pop-corn like domain embedded in a uniform Cartesian mesh. Figure 5: Poisson problem defined on a moving domain. Note that the standard embedded formulation leads to very high condition numbers, which are very sensitive to the relative position between the computational domain and the background mesh, specially for second order interpolations (). In contrast, the condition number is much lower for the enhanced formulation (the AgFEM method) and it is nearly independent of the position of the domain.

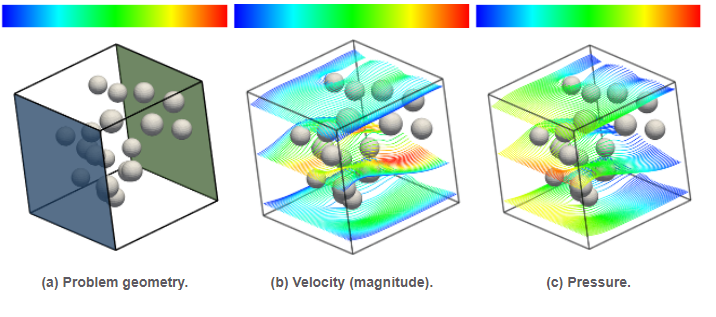

Figure 5: Poisson problem defined on a moving domain. Note that the standard embedded formulation leads to very high condition numbers, which are very sensitive to the relative position between the computational domain and the background mesh, specially for second order interpolations (). In contrast, the condition number is much lower for the enhanced formulation (the AgFEM method) and it is nearly independent of the position of the domain. Figure 6: Numerical solution of a (dimensionless) Stokes problem using the AgFEM method (streamlines colored by velocity magnitude and pressure). This computation is carried out without constructing an unstructured body fitted mesh thanks to the application of the AgFEM method.

Figure 6: Numerical solution of a (dimensionless) Stokes problem using the AgFEM method (streamlines colored by velocity magnitude and pressure). This computation is carried out without constructing an unstructured body fitted mesh thanks to the application of the AgFEM method.Petascale-capable distributed-memory parallelization of AgFEM

The small cut cell problem of embedded methods is a major issue when dealing with large-scale simulations. In large-scale scenarios, one has to invariably rely on (preconditioned) iterative linear solvers based on the generation of Krylov subspaces (21). Krylov methods are well-known to be very sensitive to the conditioning and spectral properties of the linear system coefficient matrix. Most of the works enabling the usage of iterative linear solvers in combination with embedded FE methods consider tailored preconditioners for the matrices affected by the small cut cell problem. The main drawback of this approach is that one relies on highly customized solvers, and therefore, it is not possible to take advantage of well-known and established linear solvers for FE analysis available in renowned scientific computing packages as TRILINOS (22) or PETSc (23). The AgFEM method solves this issue at the discretization level, and thus opens the door for the efficient exploitation of state-of-the art petascale-capable iterative solvers.

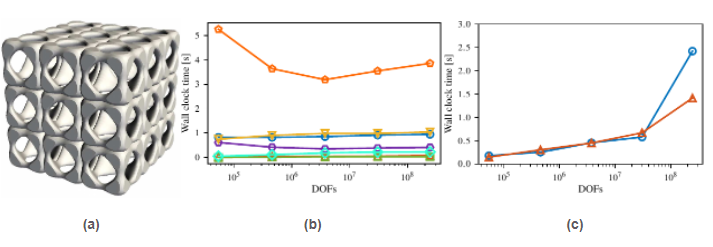

Taking this as a motivation, I have recently developed the message-passing variants of the algorithms involved in all stages of the AgFEM method (e.g., construction of cell aggregates, set up and resolution during FE assembly of ill-posed DOF constraints, etc.). Up to the fact that the processors might require to retrieve from remote processors the roots of those cell aggregates which are split among processors, this work has proven the AgFEM method to be a method very amenable to distributed-memory parallelization. In particular, it can be implemented using standard tools in parallel FE libraries, such as ghost cells nearest neighbour exchanges. I have implemented these algorithms in FEMPAR using MPI for inter-processor communications. Their high appeal at large scales has been demonstrated with a comprehensive weak scaling test up to 16K cores and up to nearly 300M DOFs and a billion cells in the Marenostrum-IV supercomputer using the Poisson equation on complex 3D domains as model problem. See Fig.7. The obtained results confirm the expectations: when using AgFEM, the resulting systems of linear algebraic equations can be effectively solved using standard AMG preconditioners. Remarkably, I did not have to customize the default parameters of the preconditioner, demonstrating that users can take what is already available out there ''out of the box''. To my best knowledge, this is the first time that embedded methods are successfully applied to such large scales. This work has been recently published at a JCR Q1-ranked journal in the field (see reference (24) for more details).

Figure 7: (a) Geometry. (b) Wall clock time in seconds in Marenostrum-IV for the major phases (except linear solver) versus scaled problem size in proportion to the number of CPU cores. (c) Linear solver wall clock times.

Figure 7: (a) Geometry. (b) Wall clock time in seconds in Marenostrum-IV for the major phases (except linear solver) versus scaled problem size in proportion to the number of CPU cores. (c) Linear solver wall clock times.-AgFEM: extension of AgFEM to support AMR

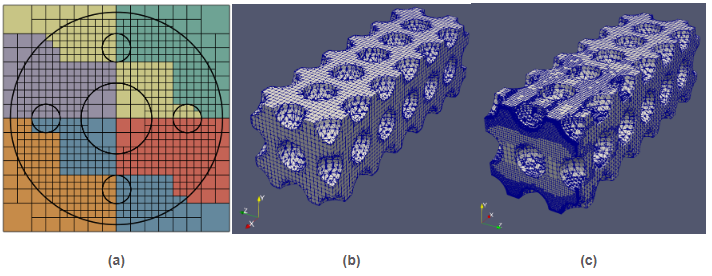

Embedded methods can be used with a variety of background mesh types. The approach that I have pursued particularly leverages octree-based background meshes using the tools covered in Sec. Scalable AMR with dynamic load balancing via forests-of-trees. This is achieved by means of a recursive approach in which a mesh with a very coarse resolution, in the limit a single cube that embeds the entire domain, is recursively refined step by step, until all mesh cells fulfill suitably-defined (geometrical and/or numerical) error criteria. See Fig.8.

Figure 8: (a) A circle domain with some circular holes inside embedded in a locally-refined quadtree-like background mesh. The colors represent the partition into 6 subdomains induced by a Z-shaped (a.k.a. as Morton) SFC. (b) Mesh used for integration purposes resulting from the intersection of the surface description of a cantilever beam with a set of spherical holes and a uniform Cartesian background mesh. (c) Mesh used for integration purposes resulting from the intersection of the surface above and a locally-adapted octree-like background mesh.

Figure 8: (a) A circle domain with some circular holes inside embedded in a locally-refined quadtree-like background mesh. The colors represent the partition into 6 subdomains induced by a Z-shaped (a.k.a. as Morton) SFC. (b) Mesh used for integration purposes resulting from the intersection of the surface description of a cantilever beam with a set of spherical holes and a uniform Cartesian background mesh. (c) Mesh used for integration purposes resulting from the intersection of the surface above and a locally-adapted octree-like background mesh.In a recent work~(12), I have addressed the challenge of developing an adaptive unfitted finite element scheme that combines AgFEM with parallel AMR. At the core of this development lies a two-step algorithm to construct the FE space at hand that carefully mixes aggregation constraints of ill-posed DOFs (to get rid of the small cut cell problem), and standard hanging DOFs constraints (to ensure trace continuity on non-conforming meshes). Following this approach, I have derived a FE space that can be expressed as the original one plus well-defined linear constraints. Mathematical analysis and numerical experiments demonstrate its optimal mesh adaptation capability, robustness to cut location and parallel efficiency, on classical Poisson -adaptivity benchmarks. See Figs. 9- 10. This work opens the path to functional and geometrical error-driven dynamic mesh adaptation with AgFEM in large-scale realistic scenarios. Likewise, it can offer guidance for bridging other scalable unfitted methods and parallel AMR.

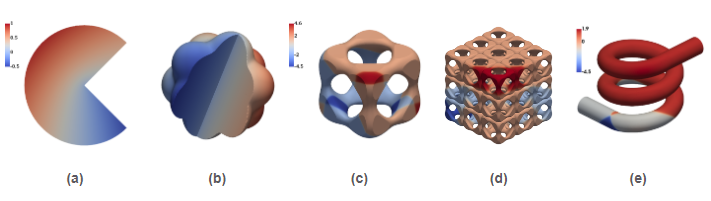

Figure 9: Geometries and numerical solution to the problems studied with tree-based -adaptive AgFEM (from here on, referred to as -AgFEM). (a)-(b) consider a variant of the Fichera corner problem, whereas (c)-(e) a Poisson problem with multiple shocks.

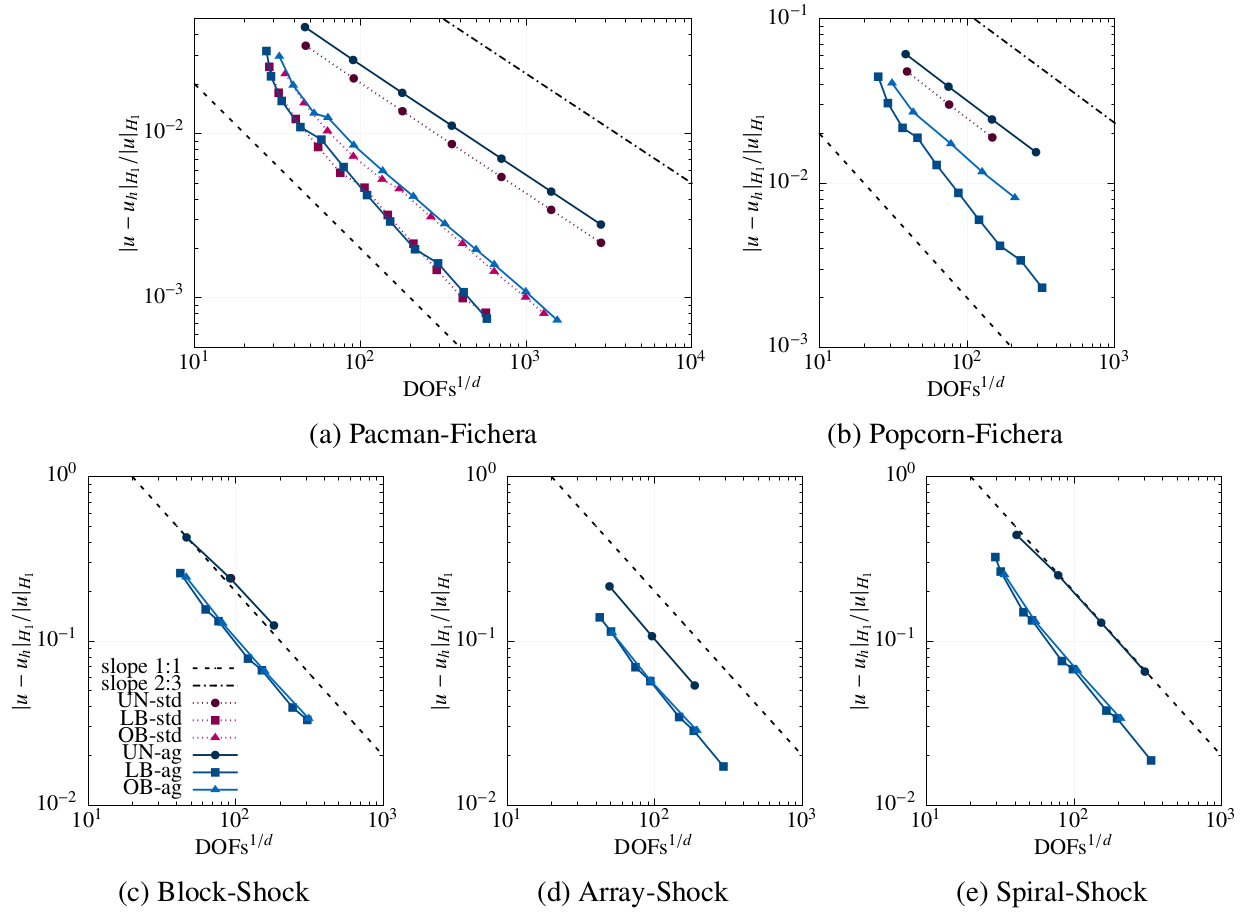

Figure 9: Geometries and numerical solution to the problems studied with tree-based -adaptive AgFEM (from here on, referred to as -AgFEM). (a)-(b) consider a variant of the Fichera corner problem, whereas (c)-(e) a Poisson problem with multiple shocks. Figure 10: For all cases in Fig.9, -AgFEM converges optimally. Moreover, in contrast to standard (std.) FEM, it does not suffer from severe ill-conditioning, that precludes generating solutions where -AgFEM can.

Figure 10: For all cases in Fig.9, -AgFEM converges optimally. Moreover, in contrast to standard (std.) FEM, it does not suffer from severe ill-conditioning, that precludes generating solutions where -AgFEM can. Figure 11: For all cases in Fig.9, -AgFEM condition number estimates are consistently well-below those of std. FEM.

Figure 11: For all cases in Fig.9, -AgFEM condition number estimates are consistently well-below those of std. FEM.Extension of -AgFEM to non-linear solid mechanics

In a close collaboration with the post-doc researcher that I have supervised during a 2-year period, we have introduced the algorithmic extensions to -AgFEM in order to deal with non-linear solid mechanics problems. This work has been published in (13). In a first stage, we have restricted ourselves to problems involving nonlinear materials whose behavior depends on the strain history. This sort of problems are used as a demonstrator, but we stress that the techniques presented can also be applied to, e.g., problems with geometric nonlinearities (i.e., solids undergoing large deformations or deflections). For such a purpose, we have devised a novel strategy that uses -adaptive dynamic mesh refinement and re-balancing driven by a-posteriori error estimators in combination with an incremental solution of the nonlinear problem (a.k.a. pseudo-time stepping). Besides, this work also addresses the functional space representation of the history variables describing the nonlinear evolution of the constitutive model. The strategy is general enough to cover a wide range of constitutive models endowed with variables of any tensorial order.

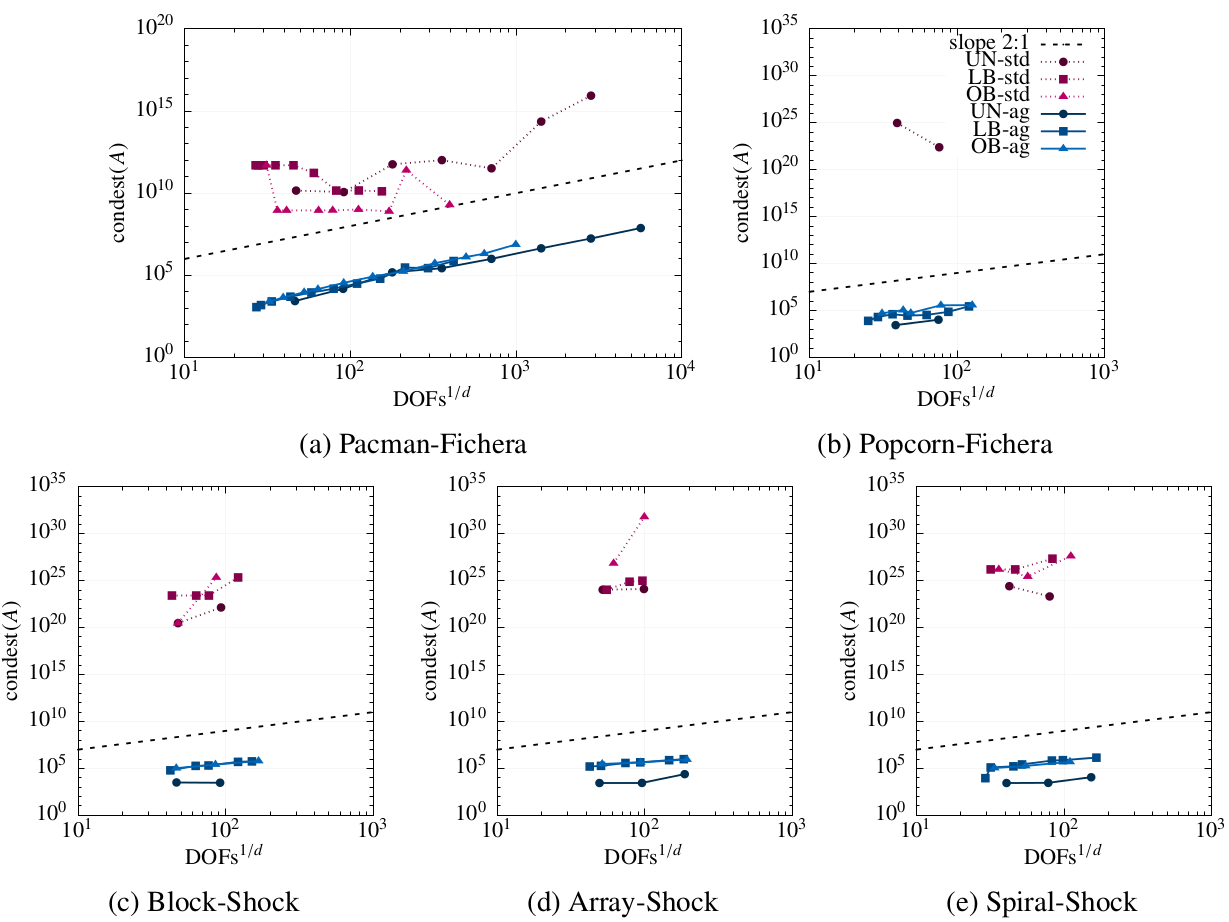

As an illustration, Fig.12 reports the results obtained from a nonlinear J2-plasticity production simulation for analyzing the strain-stress response of a Cantilever beam with spherical holes made of a relevant ductile steel alloy on the Australian Gadi supercomputer. In this experiment, as usual in nonlinear solid mechanics, a final load is imposed on the beam in load increments (pseudo time-steps), and the objective is to observe the permanent plastic deformation that the beam undergoes. Given that the problem is characterized by strain localization, the -AgFEM method is used in order to appropriately capture the geometry of the beam, in combination with AMR in order to produce a locally refined mesh while deformation is localizing in order to achieve an error tolerance while keeping computational resources low. This experiment includes all the steps in a -AgFEM simulation, namely skin mesh and background mesh intersection for each mesh adaptation cycle, setup of -AgFEM and hanging node constraints, transfer of historical variables among meshes, dynamic load-balancing at each step, Newton-Raphson linearization with line search accelerated with AMG preconditioning, etc. with localization given by a posteriori error estimators. In Fig. 12, we report the raw wall clock times of these simulations with increasing number of cores as reported by the job queuing system in Gadi for a problem with 11.687 MDOFs at the last load step. Thus, this is the true time that the user experiences when using the software. The value given in the "Serial run" row does not actually correspond to a real measurement, but to a linear extrapolation from the time measured with 192 cores. Memory consumption for was around 86% of the total amount of memory available in 4 nodes. Clearly, the most salient observation from Fig. 12c is the considerably reduction in execution times. By exploiting parallel resources, the execution time can be reduced from months to less than a couple of hours.

Figure 12: (a) Lateral view of the adapted mesh at the last load step. (b) A section of the plastic deformation of the beam. (c) Raw wall clock times with increasing number of Gadi cores. Simulation ends after 41 load steps.

Figure 12: (a) Lateral view of the adapted mesh at the last load step. (b) A section of the plastic deformation of the beam. (c) Raw wall clock times with increasing number of Gadi cores. Simulation ends after 41 load steps.Application to metal additive manufacturing processes

I have applied the tools presented in previous sections, together with other modelling and numerical discretization inventions, in order to build an accurate computational model for the simulation of metal AM processes. (I note, however, that these are essential contributions in numerical methods for the FE discretization of PDEs, and thus, their applicability goes far beyond AM computer modeling.) The advances so far in this regard have been published in two Q1-ranked JCR research journals (7, 10).

AM (a.k.a. 3D printing) refers to a set of sophisticated manufacturing technologies to build up 3D objects, on a layer-by-layer basis, from a CAD model. AM has nowadays become sufficiently mature for the 3D printing of metallic objects readily to operate in industrially-relevant applications, including the aerospace, aeronautic, automotive or medical industry, among others. The main breakthrough of AM is its ability to create cost-effective, short time-to-market objects with properties (i.e., strength, surface quality, material behavior, shape, etc.) almost impossible to produce with traditional technologies as e.g., casting or welding. However, high-energy sources used to melt metal powders during the printing process induce thermo-mechanical shape distortions and residual stresses, that deteriorate the geometrical quality and the requested material properties. The current industrial practice is based on an expensive, time-consuming, trial-and-error process, which involves the production of hundreds of uncertified copies of the object before reaching the final part. A more sophisticated approach to cope with this limitation is to shift to virtual-based design and certification, using predictive computer modeling tools. However, state-of-the-art simulation software available at the literature is still far beyond the accuracy and time frame requirements to unlock the full potential of 3D printers in real industrial use.

My work addresses, specifically, some of the challenges that arise due to the different length scales involved in the heat transfer analysis of AM processes by PBF methods. In these methods, a laser is used in order to selectively melt a new PBF layer, which is spread over the building platform with a leveling blade. In this context, typical dimensions of a printed part are on the order of [cm]. However, the relevant physical phenomena are localized around the moving melt pool [μm], following the laser spot. Likewise, the layer size is also on the order of [μm], i.e. the scale of growth of the geometry is much smaller than the scale of the part. The printing of a layer starts with the spread of a layer of powder particles across the building camber, followed by the laser-melting and solidification of the cross section of the part that corresponds to the current layer height. It is clear from here that the material can be either a porous powder or nonporous liquid/solid medium, having rather different thermomechanical properties. A high-fidelity thermal analysis requires (at the very least) that the discretization appropriately captures the interface among the porous and nonporous media. This jeopardizes the use of conventional FE methods, that require a mesh to conform to this interface at all times to provide meaningful results. Even using AMR techniques (to cope with the multiple spatial scales), this becomes a bottleneck in the simulation, because the mesh size is restricted across the whole layer, even far away from the melt pool.

The specific goal is the high-fidelity thermal simulation of the printing process of parts with non-trivial geometries. Given a set of material and printing process parameters, the outcome with relevant industrial interest is the capability to predict potential printing defects, such as excess or lack of powder fusion. This sort of insightful information is crucial for application problem experimentalists, as, e.g., those at the Monash Centre for AM, with whom I collaborate. To this end, I have developed a 3D transient thermal solver that can work on CAD geometries using the -AgFEM method on background octree-based meshes, reads the scanning sequence of the laser (using the same files as the AM machine), includes an activation procedure to determine the domain at all times, locally adapts in the melt pool via AMR and exploits distributed-memory parallelism at all stages. See Fig.13. These features, which are cornerstone for increasing modeling accuracy, and applicability to complex, industrially-relevant bodies, are not present in other AM modelling FE tools available at the literature. Indeed, the results obtained with this tool on an multi-core-based HPC cluster equipped with thousands of cores confirm that it is able to simulate AM processes with very thin layers, longer processes, higher deposition volumes, more complex geometries, significantly less time-to-solution etc., compared to the ones reached by a state-of-the-art (non-HPC, non-h-adaptive, body-fitted) software tool.

Figure 13: Snapshots of a thermal 3D printing simulation using the -AgFEM method in order to effectively represent the geometry of the growing piece.

Figure 13: Snapshots of a thermal 3D printing simulation using the -AgFEM method in order to effectively represent the geometry of the growing piece.RL2: Advanced numerical methods for the large-scale simulation of high temperature superconductors

Funding

This RL was initiated simultaneously with the FORTISSIMO EU-FP7 experiment project entitled "Multi-physics simulation of HTS devices”, in a joint collaboration of an HPC software provider (CIMNE), an application-problem specialist (ICMAB-CSIC), an HPC service provider (CESGA), and an end-user, technology-based company in the HTS sector (OXOLUTIA S.L.). The efforts were focused on the development and experimental validation of an HPC modeling tool able to equip the latter with a very valuable quantitative understanding of the design process of HTS tapes and bulks, towards the improvement of its HTS-based products, thanks to a fast and high-fidelity virtual prototyping compatible with time-to-market restrictions. In the course of this project, I led a small team within my local institution (1x PhD student, and 1x scientific software engineer) towards the achievement of the project goals. Despite being a high-technology-transfer potential, with a medium-low research component project, these joint collaborations have equipped my team with very insightful feedback to support this RL, namely: (1) deep expertise regarding the highly challenging physical processes, and accompanying PDE-based mathematical models, which are involved in the simulation of HTS tapes and bulks; (2) the necessary equipment required to perform experimental validation tasks of the software tools grounded on the research outputs of RL2.

Publications

The research work I developed so far within RL2 has resulted in 2x research manuscripts published at Q1-ranked JCR journals~(25, 26).

Motivation, research work description, and outcomes

A high temperature superconductor is a material that reaches the superconductor state at temperatures above the liquid nitrogen boiling temperature of 77K, i.e., far beyond the range of critical temperatures needed by conventional superconductors to reach the superconductor state (from around 20K to less than 1K). PIT (Powder In Tube co-extrusion and lamination) and coating technologies have allowed the development of wires and tapes able to substitute copper and conventional conductors in the manufacturing of cables and coils. In the present, the preferred format for these advanced materials is in the shape of flexible metallic tapes. The benefits of using HTS materials mainly stem from the resistance-free characteristics of HTS wires coupled to its excellent performance in high magnetic fields. Its range of application goes from very high field coils used for confining magnetically the hot plasma in future nuclear fusion reactors (like ITER or DEMO), energy storage or high resolution MRI, to motors, generators, cables, transformers or sensors and electronic devices. In all of the above applications, magnetic field, current density, temperature, heat generation, and mechanical stresses related to the high forces developed during cooling down and the working conditions at high magnetic fields should be considered.

Computational tools are a powerful technique to simulate the behavior of HTS tapes by solving the system of PDEs that governs the problem. FE methods are commonly used in HTS modeling, because they can handle complicated geometries, while providing a rigorous mathematical framework. However, HTS modeling is an extremely challenging, computationally-intensive task. It is a multi-physics (involves electromagnetism, thermodynamics and mechanics), multi-scale (microns to millimeters), extremely non-linear problem. An appropriate formulation of the system of PDEs governing the problem, the FE discretization scheme, and non-linear solver thus plays a crucial role in order to obtain meaningful results. The standard practice regarding computational modeling in the HTS community consists on the usage of commercial software (such as e.g., COMSOL). These software packages are not typically equipped with HTS-tailored, state-of-the-art numerical methods, and are either sequential or poorly scale beyond a moderate number of cores. As a consequence, a myriad of simplifications are introduced in the computational model, and computing times span from days up to some weeks, even for very simplified 2D models. In order to by-pass this bottleneck, the research work that I have carried out pursues the development of advanced, HTS-tailored numerical algorithms, and HPC software tools for the large-scale simulation of HTS tapes and bulk on high-end computing environments.

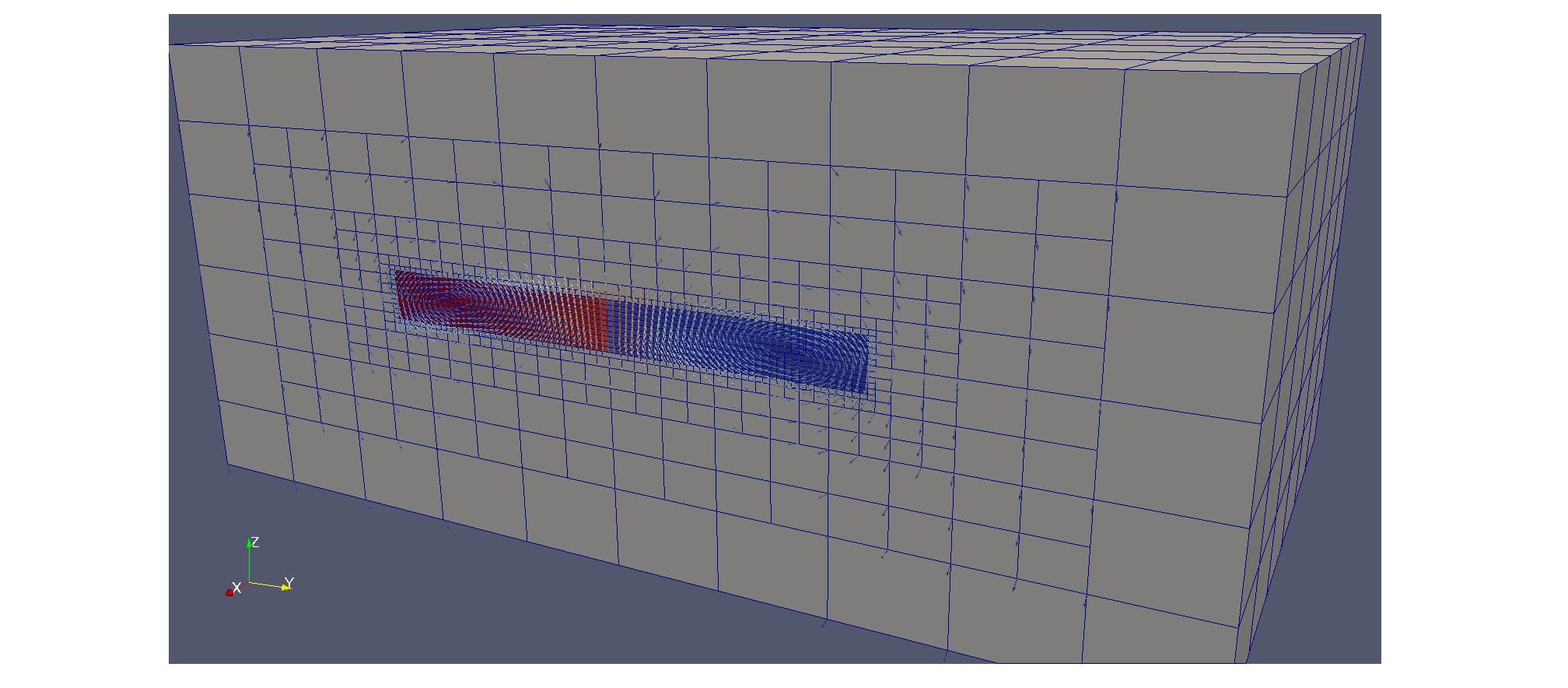

Figure 14: Current density profile (color map) computed by the HTS modeling tool for a toy 3D problem at a given fixed time.

Figure 14: Current density profile (color map) computed by the HTS modeling tool for a toy 3D problem at a given fixed time.One of the outputs by this RL is a novel HPC software tool, grounded on FEMPAR (see Sec. ), for the non-linear eddy current, AC loss large-scale modelling of HTS tapes and bulks. The hallmark of this tool, compared to any other available in the literature, is its ability to combine arbitrary-order Edge FEs for the Maxwell Equations with AMR on octree-based meshes (see Sec.) while exploiting message-passing parallelism in all stages of the simulation pipeline (26), and a novel 2-level BDDC preconditioner that I have developed for the linearized discrete Maxwell Equations with heterogeneous materials able to scale up to dozens of thousands for computational cores (25). The problem to be simulated consists of a superconductor material surrounded by a dielectric (i.e., extremely high resistivity) box, ''large enough'' (compared to region spanned by the superconductor) for neglecting the effects of the superconductor magnetization on the boundary of the dielectric box; see Fig.14. The system of PDEs selected for describing this problem is grounded on the H-formulation of the Maxwell system of equations, properly extended to HTS modelling via a judiciously-selected power law to describe the electric field-current density relation (see (26) and references therein). This latter constitutive equation, which is required to describe the penetration of the magnetic flux and induced currents on HTS materials, transforms the linear system of Maxwell equations into an extremely non-linear problem.

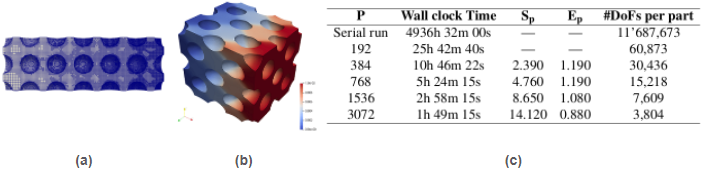

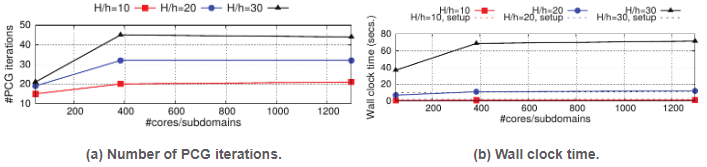

The FE discretization and solver machinery is based on HTS-tailored, state-of-the-art numerical algorithms. First, the magnetic field is discretized using curl-conforming, Nèdèlec (a.k.a. edge) FEs of arbitrary order. The usage of this sort of FE spaces is absolutely essential for the robust and accurate modelling of HTS devices, as they relax continuity-constraints, compared to nodal Lagrangian FEs typically used in the structural mechanics community, by letting the normal component of the discrete magnetic field to be discontinuous across the interface of two media (i.e., superconductor-dielectric box) with highly contrasting properties. On the other hand, parallel AMR by means of non-conforming, octree-based meshes, is used in order to tackle the multiscale nature of the phenomena, while keeping moderate computational requirements. For example, in Fig.14, magnetic field and current density have to be captured in high detail within the superconductor through a high resolution mesh, while the ones at the dielectric box hardly vary, and thus a coarse-mesh resolution suffices. Finally, at the (non)linear solver kernel, I have developed a highly-scalable software implementation of the aforementioned preconditioner (grounded on the advances in Sec., tailored for the discrete curl-curl operator with heterogeneous materials (25). In a nutshell, in order to enforce the continuity across subdomains of the method, I have used a partition of the interface objects (edges and faces) into sub-objects determined by the variation of the physical coefficients of the problem. Besides, the addition of perturbation terms to the preconditioner is empirically shown to be effective in order to deal with the case where the two coefficients of the model problem jump simultaneously across the interface. The new method, in contrast to existing approaches for problems in curl-conforming space does not require spectral information whilst providing robustness with regard to coefficient jumps and heterogeneous materials. This numerical algorithm is essential in order to accelerate the convergence of the underlying iterative solver at each Newton-Raphson non-linear step, while keeping bounded the number of iterations for both higher mesh resolution, and number of computational cores. See Fig.15.

Figure 15: Weak scalability on the MN-IV supercomputer, for different local problem sizes (i.e., FEs/core), of the novel 2-level BDDC preconditioner for the discrete Maxwell equations when applied to the first linearization of the non-linear problem corresponding to the first time step in a HTS simulation.

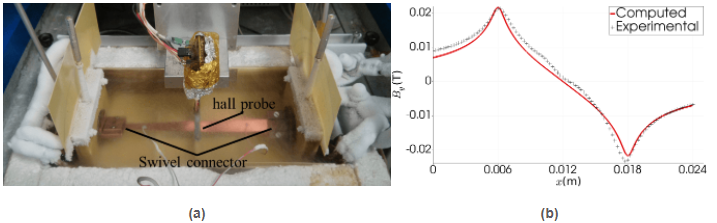

Figure 15: Weak scalability on the MN-IV supercomputer, for different local problem sizes (i.e., FEs/core), of the novel 2-level BDDC preconditioner for the discrete Maxwell equations when applied to the first linearization of the non-linear problem corresponding to the first time step in a HTS simulation.The results that my team and me have obtained with this tool on the BSC-CNS MN-IV supercomputer are very remarkable. First, it has been shown to be able to accurately model an industrially-relevant, state-of-the-art, large-scale problem in the HTS community with unprecedented resolution, and time-to-solution (25). Second, in the framework of the collaboration with ICMAB-CSIC, we could confirm that it significantly reduces computational times (with respect to a COMSOL-based solution) from weeks and hours, to days and minutes, resp., for a number of 2D toy benchmarks problem proposed by ICMAB-CSIC, while being able to successfully (accurately) model 3D problems, out of reach until today by ICMAB-CSIC. Third, the numerical tool has been validated experimentally against the so-called Hall probe mapping experiment. A high agreement of numerical results against measured data was observed; see Fig.16, and (26) for details. Fourth, although it is still a prototype, this tool is already providing insightful understanding of the electromagnetic behavior, under different design parameters (e.g., size and shape), of the HTS tapes manufactured by OXOLUTIA S.L.

Figure 16: (a)Experimental rig designed by ICMAB-CSIC in order to measure the external magnetic field produced by a transport current in a 2G HTS tape. (b)Vertical component of the magnetic field at different tape regions for a snapshot at a particular time in which the external applied current is of 400 Amperes.

Figure 16: (a)Experimental rig designed by ICMAB-CSIC in order to measure the external magnetic field produced by a transport current in a 2G HTS tape. (b)Vertical component of the magnetic field at different tape regions for a snapshot at a particular time in which the external applied current is of 400 Amperes.RL3: Software engineering of large scale scientific applications, open source scientific software

Funding

This RL was directly funded by the EU-ERC PoC project, FEXFEM-On a free open source extreme scale finite element software, in which I led a research team within the CIMNE-LSSC department (1x early career post-doc, 1x PhD. Student, and 1x scientific software engineer) towards the accomplishment of the project goals.

Publications

The research work I developed within RL3 has resulted in 4x research manuscripts published in Q1-ranked JCR journals (27, 28, 29, 30), and in the form of open source HPC software packages for the general CSE community.

Research line statement and motivation

This work is motivated by the fact that research on advanced, newly developed FE discretizations and solution algorithms for the HPC solution of CSE complex problems frequently requires innovative solutions on the software engineering aspects of a numerical software package as well, and that these latter also represent an important contribution to other researchers working in the CSE community. As an example, edge FEs for the Maxwell equations, although well-understood mathematically, are hard to implement in practice, at least in its full generality (e.g., bricks and simplices, arbitrary polynomial order, arbitrary neighbouring cells orientation, etc.). This is due to their extremely complex mathematical structure. In (29), I have presented a mathematically-supported software architecture that sheds some light into this task to practitioners working in this field by providing, among others, an straightforward manner for constructing its associated functional spaces.

A part of my research career has been focused on developing advanced mathematical software, in particular, software which can be re-used by other researchers in the community, in the seek, among others, of reproducible science. Poorly software engineered codes, rigid, non-extensible, with a limited life span, developed by within a single research group or university department for a target application problem, and/or a specific numerical method, clearly do not serve the purpose. A robust, efficient, sustainable software, engineered, among other criteria, with flexibility, usability, extensibility, composability, and interoperability in mind, resilient to new algorithmic and hardware trends, which in turn fosters collaboration among researchers from different institutions and background becomes essential. This is the ultimate goal of this RL.

Research work description, and outcomes

I am co-founder, main software architect and project coordinator of FEMPAR (30) (available at https://github.com/fempar/fempar), an open-source, HPC, hybrid MPI+OpenMP parallel, scientific software package for the numerical modelling of problems governed by PDEs on HPC platforms (from multi-core based clusters, to high-end petascale supercomputers). The first public release of FEMPAR has almost 300K lines of code written in (mostly) OO Fortran and makes intensive use of the features defined in the 2003/2008 standards of the language.

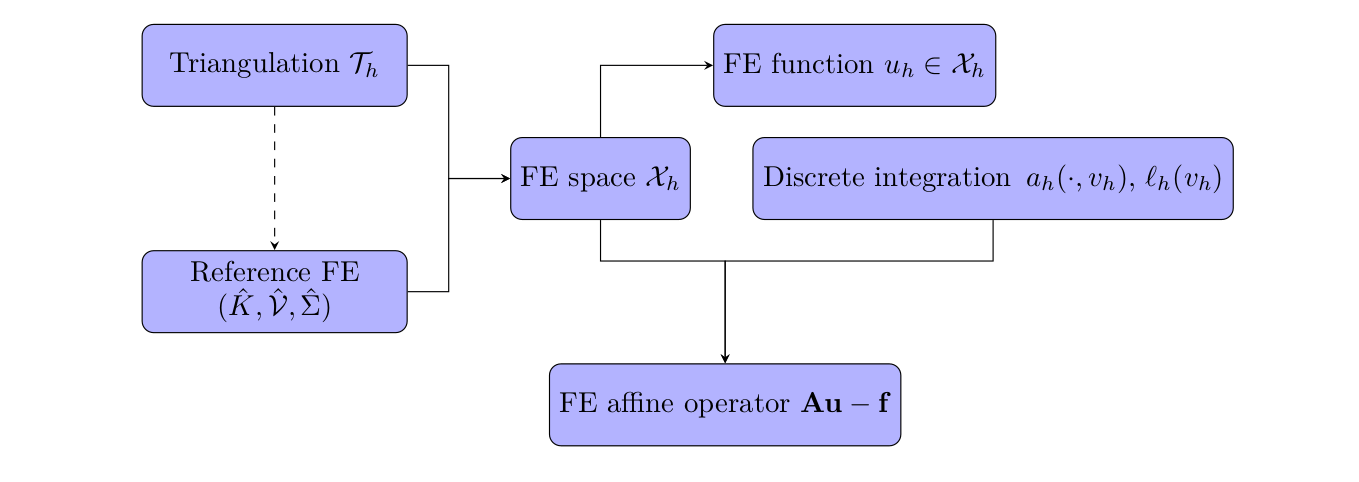

FEMPAR has a mature software architecture equipped with robust software abstractions for all the basic building blocks typically involved in a FE simulation; see Fig. for an sketch of the ones involved in the discretization of the PDE problem at hand. This software architecture has been judiciously engineered using advanced OO mechanisms (inheritance, dynamic run-time polymorphism, data hiding and encapsulation), design patterns and principles, in order to break FE-based simulation pipelines into smaller blocks that can be arranged to fit user’s application requirements. Through this approach, FEMPAR supports a large number of different applications covering a wide range of scientific areas, programming methodologies, and application-tailored algorithms, without imposing a rigid framework into which they have to fit; see e.g., the ones covered in RL1, RL2, and RL4. In seek, among others, of FEMPAR to become a community code, it is released for free for non-commercial purpose under the terms of the open source GNU GPLv3 license.

Figure 17: Main software abstractions in

Figure 17: Main software abstractions in FEMPAR and some of their relationships.There is a number of, high-quality, open source OO FE libraries available in the community, e.g., deal.II, FEniCS, GRINS, Nektar++, MOOSE, MFEM, FreeFem++, DUNE, OpenFOAM. In general, these libraries aim to provide all the machinery required to simulate complex problems governed by PDEs using FE techniques. However, in all of these libraries, the solution of the linear system is clearly segregated from the discretization step. The linear system is transferred to a general-purpose sparse linear algebra library, mainly PETSc, Hypre, and/or TRILINOS. This might limit numerical robustness and efficiency for specific applications. It in particular eludes to fully exploit the underlying properties of the PDE operator and the numerical discretization at hand to build an optimal solver. In contrast to this approach. FEMPAR’s hallmark is that it has been developed with the aim to provide a framework that will allow researchers to investigate on novel complex computational algorithms that are not well-suited in the traditional segregated workflow commented above, among other advantages. Even though every block within the library preserves modularity, the interface between discretization and numerical linear algebra modules within FEMPAR is very rich and focused on PDE-tailored linear systems.

FEMPAR has been successfully used in 40x JCR Q1-ranked research papers on different topics and application areas: simulation of turbulent flows and stabilized FE methods (31, 32, 33, 34), MHD (35, 36, 37, 38, 39), monotonic FEs (40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47), unfitted FEs and embedded boundary methods (48, 8, 9, 11), AMR (6), AM (7, 10, 49) and HTS (26) simulations, and scientific software engineering (28, 29, 30). It has also been used for the highly efficient implementation of DD solvers (50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 25) and block preconditioning techniques (71). Its users/developers span different research groups on national and international-level institutions, including UPC, CIMNE, ICMAB-CSIC, CIEMAT, ICTJA-CSIC, Czech Academy of Sciences (Czech Republic), Sandia National Labs (EEUU), North Carolina State University (USA), Duy Tan University (Vietnam), Monash University (Australia), and l’Ecole Politechnique (Paris). Besides, it has been/is being a crucial tool for the successful execution of several high-quality EU-funded projects, namely, 1x ERC starting grant, 2x ERC PoC projects, 1x EU-FP7 project, and 3x H2020 projects.

Post-doctoral researcher stage

This research stage can in turn be split into two separated periods. The first period encompasses the work initiated during a short 6-month post-doc at UJI in the context of the TEXT EU-FP7 project. During this period I initiated a RL labeled as ''RL5'' below (see Sec.). The second period, much longer, spans 2011-2015, at Barcelona, Spain, where I developed the bulk of my post-doctoral research career. During this period, I have worked for two different institutions, namely CIMNE and UPC. The position at UPC was funded by two competitive post-doctoral research grants I was awarded, by UPC and AGAUR (Generalitat de Catalunya), respectively, with an aggregate amount of 108K€. In collaboration with renowned researchers from these institutions, and other EU and international-level ones, I contributed with success to several topics within the framework of the FE approximation of large-scale PDEs, towards achieving to a large extent a position of professional maturity and independence. Besides, I have participated as a researcher in several national and high-quality funded EU-level research projects (2x national projects, 1x ERC Starting Grant, and 1x EU-FP7). During this period, I carried out the line labeled as ''RL4'' below (see Sec.).

RL4: Advanced numerical methods for the large-scale simulation of nuclear fusion reactors breeding blankets

Funding

This RL is framed within my participation as a researcher in several national and EU level projects: (1) the Spanish MICINN’s CONSOLIDER-TECNOFUS project, in which I worked in collaboration with the Fusion National Laboratory at CIEMAT on the computer simulation of some concepts of TBMs for the ITER project; (2) the ERC Starting Grant COMFUS, to support basic research in the development and mathematical analysis of FE techniques for Magneto-Hydrodynamics (MHD) and plasma physics simulations, as well as in optimal parallel solvers and HPC tools for the simulation of realistic fusion technology problems; (3) the Spanish National Plant project FUSSIM, aimed at the development of MHD-magnetic-structure solvers for the accurate structural analysis of the BBs, and (4) the EU FP7 project NUMEXAS, in which a partnership composed of several EU research-oriented, and private sector institutions (from Spain, Greece, and Germany) focused their joint interdisciplinary efforts towards the next generation of advanced numerical methods and computer codes able to efficiently exploit the intrinsic capabilities of future Exascale computing infrastructures for grand-challenge problems arising in CSE. While performing this research, my position at UPC was funded by two competitive post-doctoral research grants I was awarded, by UPC and AGAUR (Catalan Government), respectively, with an aggregate amount of 108K€.

Publications

The work I developed as part of this RL resulted in 7x papers published in Q1-ranked JCR journals (50, 51, 52, 53, 57, 58, 71) , and 1x paper in a Q3-ranked one (54).

Research line statement and motivation

The ultimate goal of RL4 is the realistic simulation of liquid metals in BBs that surround the plasma in a nuclear fusion reactor. The BB is one of the key components in a fusion reactor. It consists of a set of micro-channels filled with a liquid metal (Pb-Li) that acts as a neutron shielding, extracts the energy out of the reactor, and produces and extracts Tritium, needed to maintain the plasma. In the frame of the ITER project (See https://www.iter.org/ for more details.), the experimental fusion reactor will not have BBs, since the ITER reactor will not be a complete fusion reactor. In any case, it will have the so-called TBMs that will be similar to BBs, and will allow evaluating the feasibility of different BB concepts. There are many TBM designs in progress, but it is unclear whether or not the designs studied nowadays will be useful for the development of BBs. Since the facilities required to carry out experimentation will not be operative in the forthcoming decade, numerical simulation of TBMs is the only way to aid in their design process. The liquid metal flow inside the blanket channels can be modelled through the thermally-coupled incompressible inductionless MHD system of PDE equations. This model describes the dynamics of an electrically conducting fluid under an external electromagnetic field with thermal coupling, where the magnetic field induced by the currents is negligible with respect to the externally applied one. The numerical FE solution of these equations is a computationally-demanding task. Apart from the multi-physics, highly non-linear nature of the system, it involves length and time scales of very different orders of magnitude, leading to truly multi-scale problems. Implicit algorithms are able to obtain meaningful large-scale results without the need to solve for the smallest scales due to stability constraints. However, they require to solve a huge and sparse (non)linear system at every time step, so that massively parallel and scalable algorithms/software as well as the computational power provided by state-of-the-art petascale computers is needed.

Extreme-scale preconditioned iterative linear solvers for one-physics problems

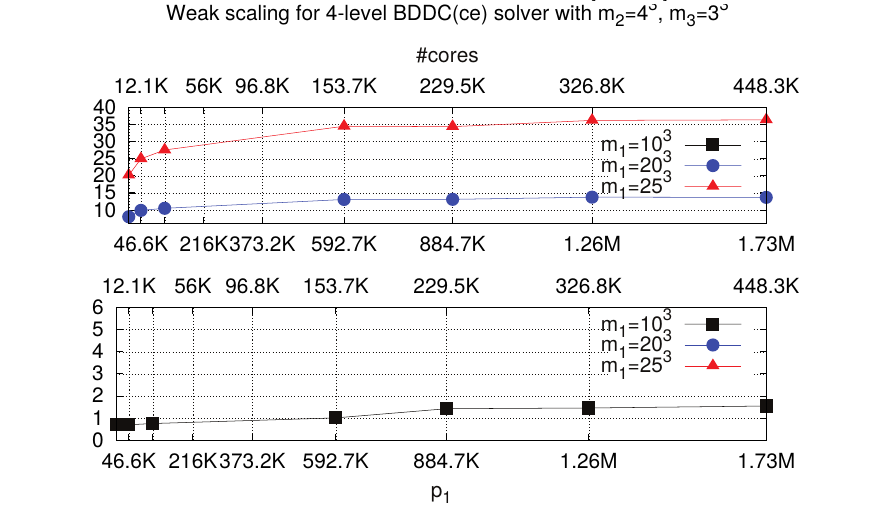

The block recursive LU preconditioners discussed below, at the preconditioner level, the computation of every physical variable in a multi-physics problem. Thus, even though the starting point is a complex multi-physics problem to be solved, the application of the block LU preconditioner only involves the solution of one-physics problems, usually Poisson or CDR-type problems (diagonal blocks). Next, these one-physics problem are replaced, e.g., by a highly scalable parallel solver, in order to end up with a truly scalable MHD solver. In this context, a remarkable contribution within RL4 is as follows: I have been able to demonstrate the high-suitability of Multilevel BDDC preconditioners for the efficient/scalable solution of huge sparse linear systems arising from the FE discretization of linear elliptic PDEs (e.g., Poisson, Elasticity) on current state-of-the-art petascale world-class massively parallel processors. In order to achieve this goal, I have proposed a novel bulk-asynchronous, fully-distributed, communicator-aware, inter-level overlapped, and recursive algorithmic adaptation of MultiLevel BDDC preconditioners towards extreme-scale computations which has been shown to efficiently scale up to the 458K cores of the IBM BG/Q supercomputer installed in JSC, Germany, in the solution of linear elliptic PDE problems with dozens of billions of unknowns; see Fig.18. This work was published in a series of two papers at the SIAM Journal of Scientific Computing~ (50, 53). This sort of solvers are not only of paramount importance for large-scale MHD simulations, but are at the core of many large-scale scientific codes grounded on the FE solution of PDE problems. Indeed, extreme-scale solvers for sparse linear algebra is a broad and timely subject of strategic importance, as evidenced by the significant increase in investment during the past few years. Thanks to these outstanding results, FEMPAR has been qualified for High-Q club status (59), a distinction that JSC (Germany) awards to the most scalable EU codes.

Figure 18: Weak scalability (computation time in seconds) for a 4-level MLBDDC preconditioner in the solution of a Poisson problem up to 20 billion DOFs on 1.8M MPI tasks at the IBM BG/Q supercomputer.

Figure 18: Weak scalability (computation time in seconds) for a 4-level MLBDDC preconditioner in the solution of a Poisson problem up to 20 billion DOFs on 1.8M MPI tasks at the IBM BG/Q supercomputer.Within this line of research I have also contributed to the rehabilitation of the Balancing Neumann-Neumann preconditioner as an efficient preconditioning strategy for large-scale fluid and solid mechanics simulations (51), and to the scalability boost of inexact BDDC preconditioners (54). Besides, I have developed a new variant of BDDC for multi-material problems~(57)}. The coarse space in this preconditioner, referred as PB-BDDC, is based on a Physics-Based aggregation technique, and unlike BDDC solvers based on adaptive selection of constraints, does not involve expensive eigenvalue solvers. The new preconditioner have been shown to be robust and scalable for materials with heterogeneous properties. Besides, in (57), it is compared against a state-of-the-art, highly efficient MPI implementation of an adaptive-coarse-space BDDC preconditioner implemented in the PETSc software package from ANL. For the largest-scale problem evaluated (more than a half billion DOFs on 8.2K cores), the new algorithm/software combination is 8x times faster, while consuming significantly less memory resources. Finally, in (58), I have also developed an enhanced variant of the original BDDC preconditioner that is able to eliminate the condition number matrix dependence on the ratio among the subdomain and mesh resolutions.

A novel stabilized FE formulation and block LU preconditioning formulations

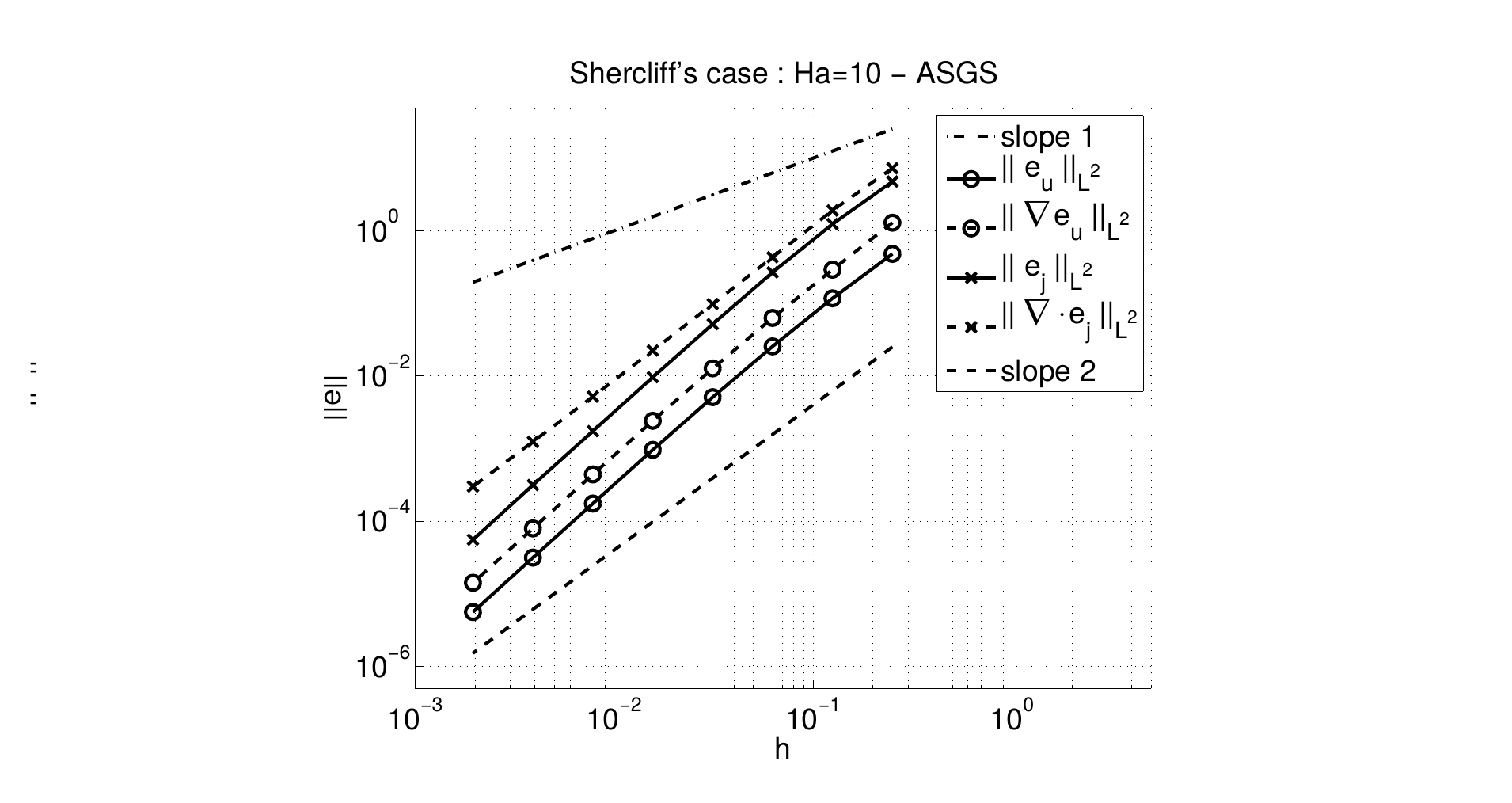

The Galerkin FE approximation of this problem by means of grad-conforming Lagrangian FE spaces faces several well-known drawbacks. First, convective dominated flows may lead to oscillations because the system loses its elliptic nature. Second, a strong coupling between the two saddle-point subproblems, the hydrodynamic and the magnetic ones, may introduce numerical instabilities when solving the resulting linear systems of equations. Finally, in order to have a well-posed problem, the classical inf-sup conditions between the approximation spaces for the velocity and the pressure must be satisfied. This also applies to the current density and the electric potential as well. There exist several options to circumvent these difficulties, with stabilization methods being one of the most widely used. In order to cope with this problem, a first remarkable contribution within RL4 comes in the form of a new stabilized, variational multiscale-like FE scheme tailored for this system of PDEs; see Fig.19 for the convergence analysis of the new method for the so-called Shercliff’s benchmark, and (71) for further details. The most particular feature of these approaches is the current density being treated as an actual unknown of the problem. This is in contrast to the typical approach based on simplifying the original problem by decoupling the fluid and electromagnetic problems. For large Hartmann numbers (in fusion BB simulations these are in the order of -), this latter approach can only work for extremely small time steps, and it cannot be used for steady problems.

Figure 19: Optimal convergence for the -norm of the velocity error and its gradient, and the current density error, and its divergence.

Figure 19: Optimal convergence for the -norm of the velocity error and its gradient, and the current density error, and its divergence.A remarkable contribution within RL4 comes in the form of algorithmically scalable (i.e., mesh resolution independent) preconditioning algorithms for the discrete operators resulting from these new FE schemes. The novel approach that was proposed in order to tackle these highly-coupled, multi-physics problems is based on an approximate block recursive LU factorization of the system matrix. An abstract setting presented in (71) enables the application of this idea to other multi-physics problems like resistive MHD or liquid crystal problems. For the particular problem at hand, I derived two different preconditioners using this abstract setting. The first preconditioner, the so-called fluid-magnetic subproblem factorization (FMS preconditioner) is based on an initial factorization of the system matrix into fluid and magnetic subproblems. The second preconditioner, the so-called Field-Lagrange multiplier factorization (FLM preconditioner), segregates at the first level field variables (velocity and current) from Lagrange multiplier-type variables (pressure and electric potential). The key point for these preconditioners to be efficient relies in obtaining a good approximation of the Schur complement for all 2x2 systems. In order to define the Schur complement approximations, I extended the ideas used for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations to the inductionless MHD system. The efficiency and robustness of the FMS and FLM block LU recursive preconditioners was confirmed with respect to both mesh size and Hartmann number by means of a detailed set of numerical tests (71).

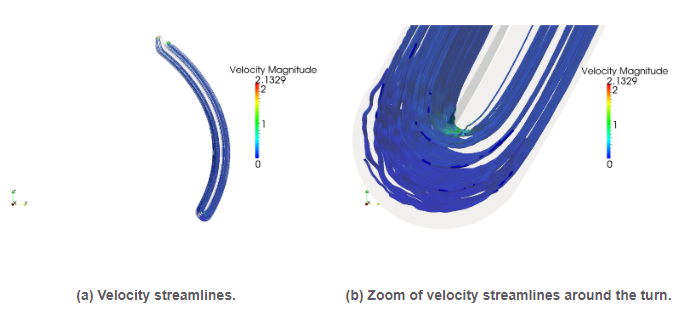

Large-scale TBM simulations

The combination of all the novel algorithms developed within this RL has enabled large-scale realistic BB simulations up to scales and (high) Hartmann numbers unprecedented in the computational fusion community. In particular, the HPC software tool developed (grounded on FEMPAR, see Sec.), was applied to the MHD simulation of a dual-coolant liquid metal blanket designed by the Spanish BB Technology Programme TECNOFUS (details available at http://fusionwiki.ciemat.es/wiki/TECNO_FUS). The simulation of the TECNOFUS TBM is a very challenging task due to its extreme physical conditions. As an illustration, the dimensionless numbers corresponding to the physical properties of the fluid (a liquid metal, the alloy Pb-15.7Li) are as high as Reynolds number of and a Hartmann number of. Fig.20 shows the fluid velocity streamlines computed by the HPC simulation tool (at a fixed snapshot in time) for the whole TBM, and a zoom of those around the turn. This simulation was performed on a 100 million unstructured tetrahedral mesh on 4096 CPU cores of the MN-III supercomputer (at BSC-CNS), with a time step size as large as 0.025 secs.

Figure 20: Simulation results for the Tecnofus TBM

Figure 20: Simulation results for the Tecnofus TBMRL5: Leveraging novel parallel programming models in legacy parallel scientific software packages

Funding

This research line was initiated during a short 6-month post-doc position at UJI in the context of the EU-FP7 project TEXT-Towards EXaflop applicaTions, with tight collaboration with Profs. Jesús Labarta and Rosa M. Badia (BSC-CNS, Barcelona, Spain), and researchers from other EU partners.

Publications

The work developed resulted in 1x paper published in a Q1-ranked JCR journal (60), and 1x article published in a peer-reviewed book series (61).

Research line statement

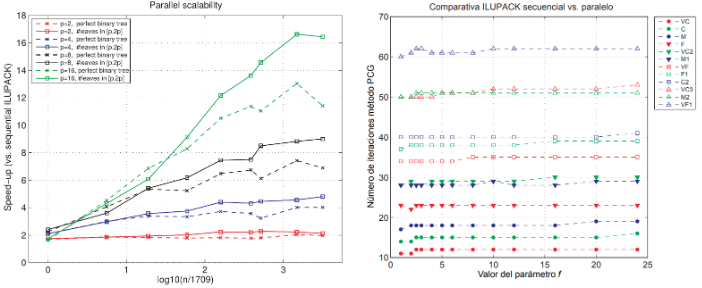

The main aim of this RL was to demonstrate the ability of a novel parallel programming model, based on the many-task asynchronous execution of parallel tasks, namely OMPSs, to leverage the performance and scalability of a set of parallel software packages/libraries judiciously selected by the high impact of the application problems they are able to solve in their respective scientific communities.

Outcomes

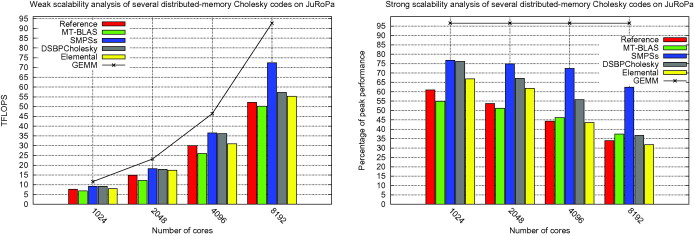

I demonstrated the ability of OMPSs to drastically boost the performance and scalability of ScaLAPACK, the de-facto standard library for dense linear algebra on distributed-memory computers. Computational kernels in ScaLAPACK are at the core of several fast solver algorithms of paramount importance in CSE, such as sparse direct solvers, domain decomposition or AMG preconditioners, and it is distributed as part of software packages with high impact on the community, such PETSc3 or TRILINOS4 from ANL, and Sandia US national labs, resp. However, ScaLAPACK was developed in the mid 90s, when a single processor (CPU) per node was mainstream, and thus are not well-suited to leverage the intra-node concurrency of as-of-today clusters nodes equipped with multicore technology. The work opened the door to reusing legacy libraries by introducing up to-date techniques like look-ahead and dynamic out-of-order scheduling that significantly upgrade their performance, while avoiding a costly rewrite/reimplementation. Fig.21 reports the strong scalability (percentage of machine peak performance versus number of cores) of the developed software (blue color), compared to other solutions available at the literature (including ScaLAPACK in red color, and Elemental library in yellow), on a HPC cluster equipped with 17.7K cores for the computation of a Cholesky factorization of a dense matrix.

Figure 21: Weak/strong scalability of proposed solution (''SMPSs'') compared with other parallel Cholesky codes on a 17.7K CPU cores HPC cluster.

Figure 21: Weak/strong scalability of proposed solution (''SMPSs'') compared with other parallel Cholesky codes on a 17.7K CPU cores HPC cluster.Pre-doctoral researcher stage

RL6: Task-parallel friendly variants of multilevel preconditioners built from inverse-based ILUs

Funding

This period started on January, 2006, when I enrolled a PhD program of the UJI at Castellón, Spain, and ended on July, 2010, where I obtained my PhD degree in Computational Science and Engineering (CSE) with honors (Cum Laude) under the supervision of Profs. Enrique S. Quintana-Ortí and José I. Aliaga. A 4-year competitive FPI fellowship awarded by Generalitat Valenciana funded my PhD. studies, and let me incorporate to the HPC\&A research group at UJI where I participated as a researcher in several regional, national, and EU-level competitive projects. The main RL was developed in tight collaboration with the group of Prof. Matthias Bollhoefer at TU Braunschweig, Germany. During this period, I also visited this group 4 times, for a total duration of 4 months. These research stays were funded by a competitive fellowship that UJI awarded to me, and a project of the “Acciones Integradas” and DAAD subprograms of the Spanish MICINN and the German Science Foundation, respectively.

Publications

This research work that I performed within this RL has resulted in 2x papers published in Q1-ranked JCR journals (62, 63), 1x chapter at the Encyclopedia of Parallel Computing by Springer (64), and 5x articles published in peer-reviewed book series (66, 67, 68, 69, 70).

Research line statement and motivation

In applications involving the discretization of PDEs, the efficient solution of sparse linear systems is one major computational task. For a large class of application problems, sparse direct solvers have proven to be extremely efficient. However, the enormous size of the underlying applications arising in 3D PDEs requires fast and efficient solution techniques. This in turn demands for alternative approaches and, often, approximate factorization techniques, combined with iterative methods based on Krylov subspaces, reflect an attractive alternative for these kind of application problems. With this in mind, the main RL developed during my predoctoral research was devoted to the design, development, and HPC software implementation of novel task-parallel friendly variants (thus amenable for the efficient exploitation of parallel computers) of multilevel preconditioners constructed from inverse-based ILUs.

Research work description, and outcomes

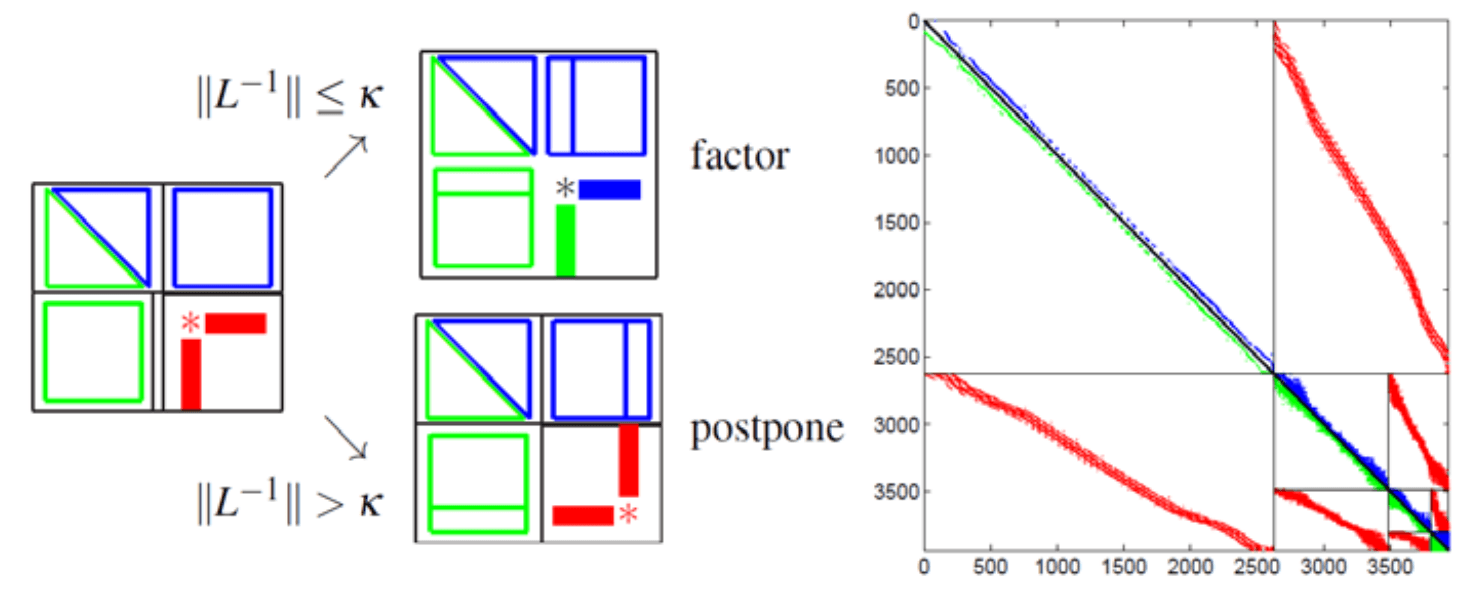

Figure 22: Left: ILUPACK pivoting strategy. Right: multilevel preconditioner.

Figure 22: Left: ILUPACK pivoting strategy. Right: multilevel preconditioner.Multilevel preconditioners constructed from inverse-based ILUs lay the foundations for the software package ILUPACK. ILUPACK is the abbreviation for Incomplete LU factorization PACKage. It is a software library, written in Fortran77 and C, for the iterative solution of large sparse linear systems. The first release of ILUPACK was launched in 2004 by Prof. Bollhoefer, and was restricted to sequential computers. Since then, it has been improved in a number of ways, including its ability to efficiently exploit parallel computers. This latest feature is the main software outcome of my PhD. thesis. ILUPACK is mainly built on ILUs applied to the system matrix in conjunction with Krylov subspace methods. The fundamental difference of ILUPACK is the so-called inverse-based approach. This approach consists on extracting information from the approximate inverse factors during the incomplete factorization itself in order to improve preconditioner robustness. While this idea has been shown to be successful to satisfy this goal, its downside was initially that the norm of the inverse factors could become large such that small entries could hardly be dropped during Gaussian elimination, resulting in an unacceptable level of fill-in in the resulting preconditioner. To overcome this shortcoming, a multilevel strategy is in charge of limiting the growth of the inverse factors. For example, for preconditioning the conjugate gradient (PCG) method, ILUPACK computes an incomplete factorization , where is unit lower triangular and entries of small modulus are dropped in the course of the factorization. ILUPACK’s hallmark is to keep below a given bound . To do so, at each step, the factorization of the current row/column is pursued whenever , or postponed, otherwise, as shown in Fig.22, left. The block of postponed updates (known as Schur complement) becomes the starting matrix of the next level; see 22, right. Using this inverse-based strategy and a moderate value of (e.g. ) it can be shown that small eigenvalues of are revealed by . Thus, serves as some kind of coarse-grid system, which resembles those built by AMG preconditioners, in particular, when applied, e.g., to elliptic PDEs.

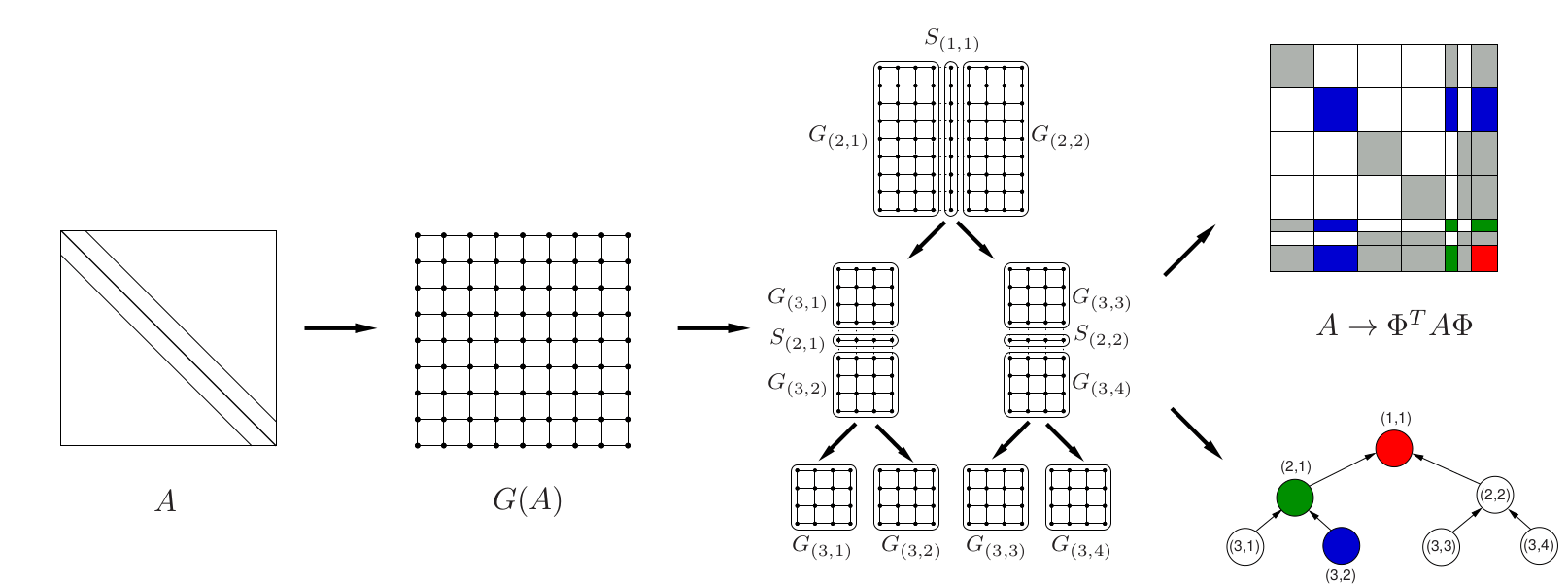

The research work carried out was focused on the design, development, and HPC software implementation of task-parallel friendly variants of the algorithm presented so far. At this point, it is important to stress that this sort of algorithm does not inherently expose parallelism readily to be exploited. Thus, it had to be transformed towards the achievement of this goal. Parallelism in the computation of approximate factorizations can be exposed by means of graph-based symmetric reordering algorithms. Among this class of algorithms, nested dissection orderings enhance parallelism in the approximate factorization of the linear system coefficient matrix by partitioning its associated adjacency graph into a hierarchy of vertex separators and independent subgraphs; see Fig.23. Relabeling the nodes of according to the levels in the hierarchy, leads to a reordered matrix, , with a structure amenable to efficient parallelization. This type of parallelism can be expressed by a binary task dependency tree, where nodes represent concurrent tasks and edges dependencies among them. State-of-the-art reordering software packages as, e.g., METIS or SCOTCH, provide fast and efficient multilevel variants of nested dissection orderings.

Figure 23: Nested dissection partitioning.